Chris Armstrong, Berenberg Stock and ESG Strategist: Robert, thank you very much for joining me. From our point of view as an investment bank, I think the pick-up in interest in this topic of sustainability and ESG over the last few years has been the biggest and quickest change in financial markets I’ve seen in 25 years. That’s also created problems for corporates, who, for 40 or 50 years, have been focused purely on shareholder returns, and are now being asked to focus on non-financial metrics. One of the things you’ve written a lot about is corporate purpose. Maybe we could start by you explaining what you think this is, why it’s so important and how you think it might help these companies in this transition.

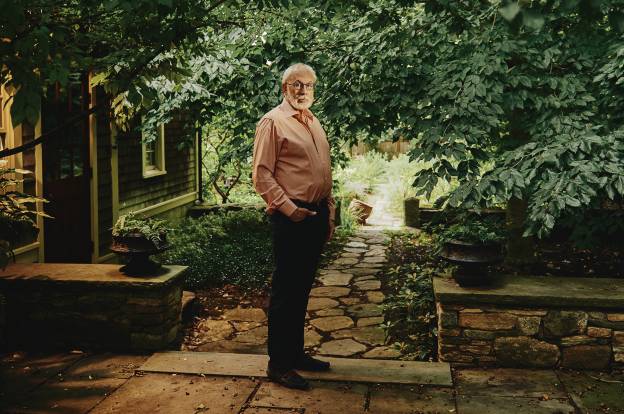

Robert Eccles, Visiting Professor of Management Practice at Saïd Business School at the University of Oxford: I’d like to just wind it back a little bit and pick up on something you said in the beginning. I do agree that this has been a major sea-change in the financial markets in the past 25 years. It’s nice to see that confirmed by a practitioner. The evolution of this is interesting. In my view, I think the corporate community was actually ahead of the investment community for a couple of decades when it came to sustainability. They were talking about it. The Global Reporting Initiative was formed in the late 1990s. Companies started doing sustainability reports. They all complained about how they had sustainability data and the investors didn’t care about it. The companies were the ones that put together the presentations for the quarterly calls. About four or five years ago there was this major shift, where the investment community got really serious about sustainability. I wrote about this. There were some important things driving that. One of the most important was that a body of empirical research was built. I did some, a friend and colleague of mine, George Serafeim, has done a lot more, to look at the relationship between sustainability and financial performance, to try and clarify the distinction between material sustainability issues that matter to value creation from a broad range of sustainability issues and philanthropy. To some extent, those still are being confounded by our Department of Labour, with this ridiculous guidance that they came out with a couple of months ago. Once the investment community started paying attention to this, it became real for companies. They then had to take it seriously themselves. As this was happening, a part of this shift, where the investment community was becoming serious about sustainability, empirical research that, over the long term, positive performance on material issues had a positive effect on financial performance, the discussion of purpose started to emerge.

You had Larry Fink with his famous letter to CEOs that he publishes every year. The initial reaction was: “Okay, what do you want us to do? Are we supposed to give up returns to do good?” He clarified that in his next letter and said: ‘No, both of these things are important.” Around the same time, a colleague of mine, Colin Mayer at Saïd Business School at Oxford, wrote this book, Prosperity, Better Business Makes the Greater Good, and I see that as the intellectual foundation for purpose. The way Colin would describe purpose is: “Why does a company exist?” Companies don’t exist to just generate profits. Companies exist to provide products and solutions for people’s needs, and to solve problems in society. Doing that in the right way is going to generate profit. There’s been this shift in mindset, almost ideology, around “what is the role of the corporation in society?” If you look at it historically, this notion that companies exist only to deliver returns for shareholders is relatively new, the past 50, 60 years. We’ve all heard about Milton Friedman and all the brouhaha around that last week. Now I think we’re rethinking the role of the corporations. Big corporations have an enormous impact in society. They create positive and negative externalities that matter to the state of the world, that matter to investors, will matter to the big passives, long-term asset owners where they can’t diversify away from system-level risk. Now you see this focus on purpose. How do companies think about the balance between short-term and long-term, shareholders and other stakeholders, how satisfying needs of shareholders generates profits over the long term. The critics say: “If you’ve got a multiple stakeholder model, you don’t have a focus. You’re not going to satisfy anybody.”

I think that’s ridiculous, even in the narrow shareholder model, there are all kinds of trade-offs that have to be made between short-term and long-term, different types of investors, equity holders, bond holders. I think we’re developing a more sophisticated view about the role of the corporation in society. That’s where you get a lot of this talk about purpose. At the same time, an awful lot of this purpose talk is only talk.

CA: I noticed your article on the Business Roundtable, where we had that announcement 14 months ago, but we haven’t seen a lot else. Can you give me examples of companies that you do think are doing it properly?

RE: I’m happy to do that, but let me whine about the Business Roundtable. This notion of a statement of purpose, I developed a number of years ago with a colleague who’s now at Federated Hermes Equity Ownership Services named Tim Youmans, it was in the context of a book on integrated reporting. We said: “The foundation is to know the purpose of the company, and that should be established by the board.” The fiduciary duty of the board is to the corporation and the shareholders, not just to shareholders. The board is the body with the highest level of accountability for the intergenerational interests of the company. We said: “A simple one- or two-page statement of purpose, that’s the framework for identifying the important stakeholders’ timeframes out of that management in terms of what the material issues were.” It was like pick your metaphor. It was Sisyphus pushing a rock uphill. It was Don Quixote tilting at windmills. We’d got to companies, and this is before Larry was talking about purpose, and they said: “Maybe but no, fiduciary duty, shareholders come first. We don’t want to do it.”

So, when the Business Roundtable came out last year, August 19th of 2019, and they came out with their statement of the purpose of a corporation, which was basically a multiple stakeholder model, I was pleased. We didn’t have anything to do with it and I thought: “Okay, they’re making a big deal of this, they’re saying that this is an enormous change from their last white paper on corporate governance, which was 1997.” It starts up, first sentence basically says the purpose of a corporation is to generate returns for shareholders, so naïve of me, I thought the dam had broken and I could go to these companies and say: “This is great, you’ve now made a public announcement to a multiple stakeholder model, stakeholder capitalism, inclusive capitalism, whatever you want to call it, shouldn’t be a big lift to get a simple company-specific, stakeholder-inclusive statement of purpose for your particular company, from your board.” No progress, none, and I thought: “Well, this is interesting.” Then I learned by gossip and then it was confirmed in a paper by some colleagues at Harvard Law School, Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita, who wrote this paper, which is a contrary view to mine basically, against stakeholder capitalism, but they went to find out how many of these CEOs went and got approval from their board to sign the Business Roundtable statement. And they wrote letters to 173 of the 181, and I think they heard from 49, one did, one CEO.

So, I’m thinking: “Okay, if this is such a big deal, and it’s the most important thing you’ve issued since 1997, maybe you’d want to run that by your board.” So, there are two possible explanations. The cynical one is that this is the American, because most of these are American companies, the imperial CEO that does whatever he or she wants, and most of them are hes. The narrative that you’re getting out of the companies that have signed this is it wasn’t a big deal. We’ve been doing purpose for years, decades, so for us to sign the statement we didn’t even have to run it by their board. Now, in the meantime there are empirical studies that have come out that show that the Business Roundtable hasn’t, on these stakeholder ratios, done better than others. I’m co-chair of something called the COVID-19 and Inequality Test of Corporate Purpose Initiative. We launch on Monday, I can send you the data, we’ve got data that shows that on a number of issues the Business Roundtable doesn’t perform any better than anybody else, MSCI has done a study, so the question is why is that? Why is that there’s all this talk about purpose, but then when you look at the data you don’t see any difference in behaviour? A reason I think is that because none of these have really instantiated this and grounded this at the very top of the corporation with the board of directors, so in a roundabout way, let me get to your statement of purpose, there are a handful of companies in the world that have published a statement of purpose endorsed by their board.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Subscribe our newsletter to receive the latest news, articles and exclusive podcasts every week