Are companies and investors just trying to make more money under the guise of ESG? Or does the call for sustainable business and investment threaten returns and thus a healthy business community and the jobs of ordinary citizens? Professor Robert Eccles, ESG guru, outlines the polarization surrounding the concept in the United States and advocates pragmatism. He also has advice for executives: “Stop being a coward.”

On December 28, 2020, Robert Eccles reached his personal best in weightlifting: a dead lift of 410 pounds. That top performance brought him into the highest echelons of his age and weight class: 99.8 percentile. “That’s more than my IQ,” he jokes. When Eccles was in the Netherlands at the beginning of 2020 for a conference and interview at Business University Nyenrode, his record was still at 340 pounds: he must have trained very hard in the first corona year.

The impressive number of extra pounds on the barbell is not the only thing that has changed in more than two years, we realize when we talk to Eccles again in the fall of 2022. The US heavyweight in sustainable business, investing and reporting has also seen the ESG (environment, social & governance) context change completely, especially in the deeply divided United States. Where ESG policies were previously seen as the panacea for all sustainability problems for companies and large investors, the concept in the States is now being attacked by both the left and right and has become a political rallying cry, Eccles said. “We are in a completely different world now.”

Science and practice

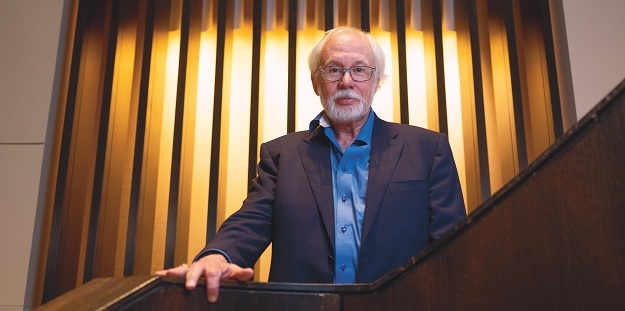

The former Harvard Business School professor is a globally recognized expert in the field of ESG and integrated reporting. He is currently a visiting professor of management practice at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford. Eccles is by no means an armchair scholar: he connects science with practice. He is an advisor to consultancy firm BCG and chairman of the first Sustainability Expert Advisory council of private equity giant KKR. He also provides consultancy services to tobacco manufacturer Philip Morris International (PMI). Eccles is used to criticism, as a columnist for the American business magazine Forbes. However, he did not anticipate the immense amount of negative reactions to his article posted on LinkedIn about why companies should support the International Sustainability Standards Board (previously published in Harvard Business Review). “Trolls spewed their vitriol; a friend showed me how to block them.”

Topology of hate

It led Eccles – a mathematician by education from MIT – to a “topology of hate” for ESG, in which he distinguishes four sets in this topological space (and a subset): the Sustainability Taliban, the Flat-Earthers, the Advocates (the Opportunists are a subset), and the Pragmatists. To be typified respectively as (in our own words): the sustainability fundamentalists, the climate crisis deniers, the ESG believers, the greenwashers, and the pragmatists, who are looking for a reasonable alternative in response to the polarization. Eccles, according to himself, falls into the latter category and thus positions himself in the heated ESG debate as a convinced sustainability pragmatist. The conversation with him is a prelude to the prestigious Piet Sanders lecture – named after the eminent corporate law attorney – at Erasmus University Rotterdam, which Eccles will be responsible for this year.

Can you elaborate on your topology of hate for ESG? How do the different entities relate to each other?

“First of all, the Sustainability Taliban: those are the purists in the sustainability debate. They hate the term ESG, because they believe that parties are only concerned with making money through ESG, not with improving the world. The sustainability efforts of companies and investors never go far enough for them: they always want more, more, more and cry out for government intervention. Their motivation is accompanied by a large ego and fiery rhetoric that excites their fellow Taliban.

Then the Flat-Earthers. They hate the term ESG just as intensely, but from a diametrically opposite point of view. The Flat-Earthers, who also love their fiery rhetoric, believe that by focusing on ESG, companies and enterprises will earn less money: the pressure to operate more sustainably threatens profitability, will destroy American business, and cost jobs. The Flat-Earthers do not believe in climate change or claim that it is not man-made or believe that the free market and technological innovation will solve it. In the United States, the Flat-Earthers have now completely politicized the concept of ESG in competing for votes with the Democrats. Former Vice President Mike Pence recently described ESG as a devious strategy by the left to push through wokeness, left-wing values, and a radical agenda for environmental and social change, as an attack on true and patriotic Americans.”

Which other sets do you find in this topological space?

“First of all, the Sustainability Advocates: they firmly believe in ESG and stakeholder capitalism. You will find them in business and the investment community, with business service providers, NGOs, and ordinary citizens. Their intention is good, but their claims can go too far: they naively present ESG as a silver bullet. They claim that as a company and investor you can make even more money with ESG than without it and improve the world at the same time. Without properly defining ESG, or substantiating their claims with facts, and without knowing how to bridge the gap between dream and practice. In doing so, they play into the hands of the criticism of both the Sustainability Taliban and the Flat-Earthers. The Advocates also have a subclass: the Opportunists. They have deftly piggybacked on the zeitgeist and have embraced ESG as a welcome marketing tool to boost their brand reputation. And then you have the Pragmatists, who I count myself among.”

Before we get into that, what does this division mean for climate and sustainability policy in America?

“The red (Republican) states mainly attack the large investors on their ESG policy. For example, the state of Texas recently passed a law that prohibits local governments from doing business with asset managers who they claim are unfriendly to fossil fuel companies—whatever that’s supposed to mean. They decry that ESG is a war against the American energy sector. For example, Mike Pence also argued that the three new directors Engine No. 1 placed on ExxonMobil’s board of directors are “environmentalists” who “are undermining the company from within.” The fact is that these directors have strong oil and gas management experience, something, amazingly enough, which has been lacking on the board until now. Another fact is that the company’s share price and projected cash flow has never been higher! Which shows how this anti-ESG campaign is based on political objectives, not facts.

Another example of the anti-ESG lobby is the crusade against the proposal that US listed companies must report on their climate policy to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Opposition comes from both the Taliban and the Flat-Earthers. For the former, it’s not nearly enough. For the latter, they don’t want any climate disclosures at all and will no doubt object to it all the way to the Supreme Court.”

How does this hate campaign affect companies’ ESG policies? Do you see the mindset in the boardrooms changing as a result?

“The heated ESG debate may be causing uncertainty in the boardrooms: is ESG still a good thing or not? But I don’t think this will make companies suddenly scale back on their climate efforts, or stop reporting on their CO2 emissions. The debate may even have a positive effect: countering greenwashing through awareness among boards that sustainability policy is not about publishing a glossy report with beautiful pictures of a blue sky, clear water, children playing and people from all kinds of cultures, but for actual long-term value creation.

At the moment, however, it is not corporations, but the big investors that are the main target of the Taliban and the Flat-Earthers. They argue that, for example, pension funds do not fulfill their fiduciary duty to manage the funds entrusted to them as well as possible: if they stop investing in fossil energy, this would be at the expense of the return and so the level of pensions. While you can of course also argue that you are not fulfilling your fiduciary duty if you invest heavily in the oil and gas industry, because that entails risks that can seriously threaten future returns.”

What role can a pragmatic approach play in the polarized ESG debate?

“At the heart of the debate is the difference between single and double materiality. The first concerns material climate risks that can negatively affect the value of the company, the second concerns material negative effects of the company’s activities on the external environment. The Sustainability Taliban believes that companies should start reporting on that external impact, on double materiality. The Flat Earthers see this as politically fueled environmental activism with the aim of destroying companies. They oppose it and do not want to go beyond single materiality reporting. As a Democrat, I co-wrote a piece with Republican Dan Crowley in which we propose a pragmatic solution that both sides can agree on. In it we say: go back to basics, let companies simply report on risks that shareholders consider material, whether or not climate-related. If you look at the oil and gas industry through those pragmatic glasses, for example, you will see that ExxonMobil scores a lot better on material issues than electric car manufacturer Tesla, which is making a mess of the social dimension of responsible entrepreneurship. You have to approach it with common sense and facts, not from ideology and emotion.

Over the next few months, Dan and I will be doing some sort of campaign. We will visit industry associations, the staff of senators and CEOs to explore the common ground: what can we agree on? We should not use the term ESG, because then everyone will get angry. Just drop that term! It would also be more effective to frame climate change differently and instead use words like energy security, employment and living standards. A new, pragmatic narrative must emerge in the public domain.”

At the private equity firm KKR you are chairman of their Sustainability Expert Advisory Council (SEAC). What role does the council play?

“In my view, private equity investors can play a leading role in sustainability, precisely because they primarily focus on value creation and have control of the asset. As members of KKR’s Sustainability Expert Advisory Council, we act as both constructive advisors and critics. The composition is very diverse. From labor and workforce to data responsibility to climate, we have a good group that brings a wealth of experience. Our job is to provide our individual perspectives to bolster KKR’s expertise and encourage them to look at whatever issue we are discussing from a 360-vantage point: why are you doing this or not, have you thought of this? KKR has always been open to our outside perspective and willing to listen when there is an uncomfortable message. And I think that’s a good thing that they are intuitively looking for other viewpoints to often challenging topics.”

You also advised tobacco manufacturer Philips Morris International (PMI). What practical dilemmas were you confronted with?

“PMI is candid about the external impact they have as a company: smoking causes disease and kills people. They express their ambition for a smoke-free future and say that with the right regulatory encouragement and support from civil society, they can see an end to the sale of cigarettes in many countries within 10 to 15 years. They are transforming to achieve that goal by developing smoke-free products that are less harmful than cigarettes for adults who would otherwise continue smoking, and have linked the reward criteria to this and provide insight into progress in an integrated annual report.

Cynics say they got those people addicted to cigarettes and now they’re just selling them another way to get their nicotine. But then I say: a billion people still smoke cigarettes, do you know another way to solve that problem? If the sector itself doesn’t commit to that, I don’t see it changing. And it’s very clear that exclusion by investors isn’t going to solve the problem. Plus, if a controversial tobacco company can make such a transformation, other companies certainly can. There is, however, a limit to my involvement as a consultant, yes. If PMI would get involved in a project that means the end of the pursuit of a smoke-free future, then I’m gone! Then I no longer want to associate my name with that.”

In the Netherlands, the court has ruled that Shell must tighten up the sustainability targets. What do you think of that?

“I find it fascinating. In effect, the judge said: protecting the quality of life is more important than creating value for shareholders as a company. And if that comes at the expense of profitability, that’s not our concern. It is an interesting example of how legislation, regulations, and case law can be used to tell companies that they are responsible for their impact on the external environment and what they should and should not do with regard to sustainability. This also raises the question of whether we should fundamentally rethink company law to do justice to the changing role of companies in society and developments such as stakeholder capitalism and long-term value creation. Incidentally, I found it ironic that the court ruling concerned Shell, because that company is moving faster in the transformation to new energy than, for example, ExxonMobil.”

Finally: how do you think company executives should position themselves in the sustainability debate?

“Be brave, stop acting like a coward. Address the Sustainability Taliban: you expect too much from us as a company, we are doing what we can. Also speak to the Flat-Earthers: we are not guided by some kind of ‘woke agenda’, but by value creation. Outline the business case: indicate that your sustainability efforts as a company enable you to captivate and capture the minds of millennials and through this create better performance. Focus on just four or five things and dare to say: we can’t please everyone, if you don’t like it, that’s your problem.’ In short: ‘Speak up!’”

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Subscribe our newsletter to receive the latest news, articles and exclusive podcasts every week